Malolactic fermentation turns malic acid into lactic acid, releasing heat and sometimes diacetyl. The sweet spot for a healthy conversion is roughly 18–22 °C, while cooler temperatures, lower pH, and sulfur dioxide can slow or stop it. Winemakers use it to soften acidity and shape texture, especially in Chardonnay, while many aromatic whites skip it to stay crisp.

MLF in plain language

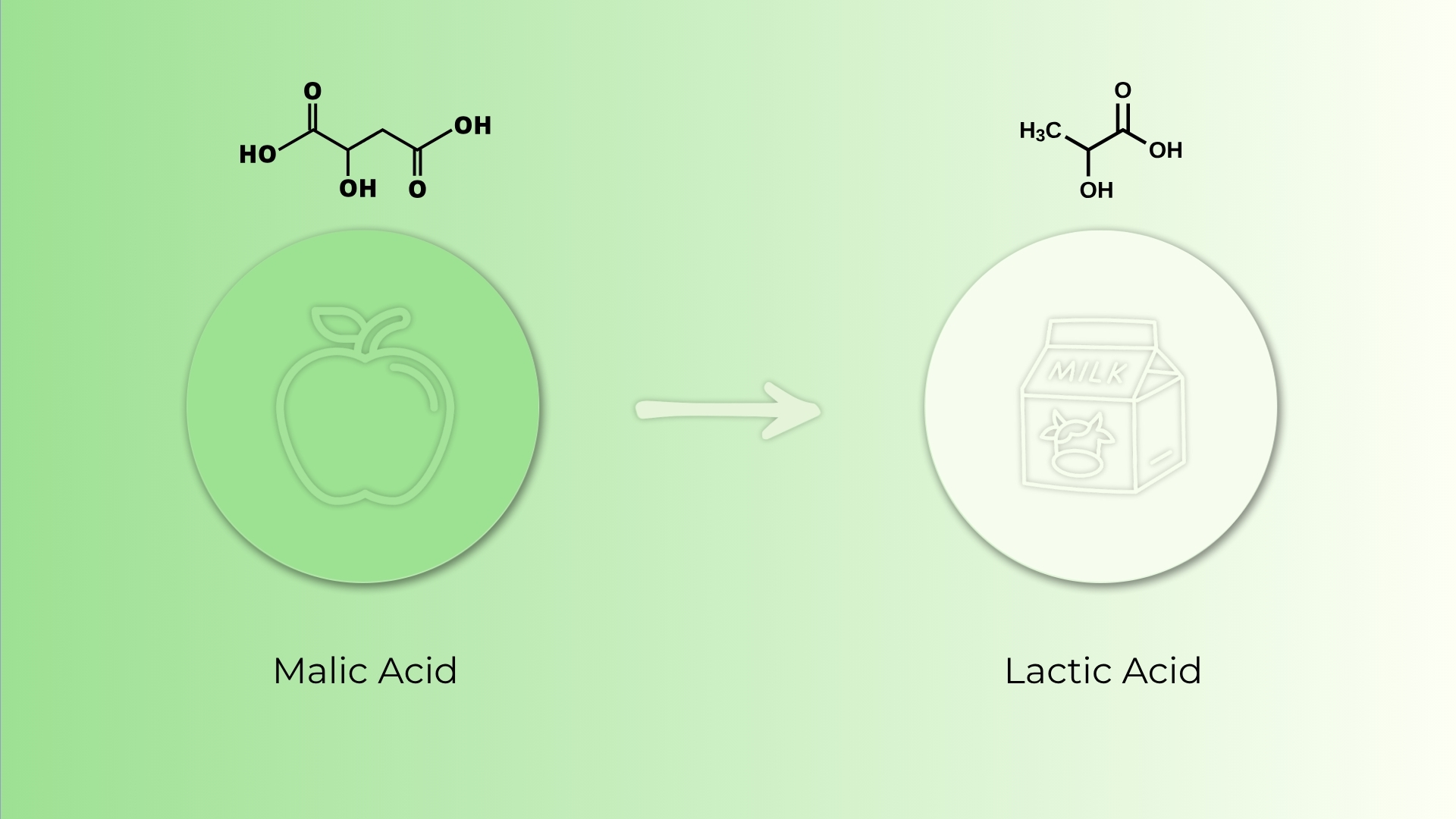

Malolactic conversion is not a yeast fermentation. It is a bacterial conversion, usually led by Oenococcus oeni. The bacteria eat sharper malic acid and produce softer lactic acid and carbon dioxide. The result is a wine that feels rounder on the palate and sometimes shows a creamy, buttery note if diacetyl is present.

If you like analogies, think of malic as green‑apple tartness and lactic as the gentle tang in yogurt. Moving from one to the other changes the wine’s posture from upright to relaxed.

The key numbers and conditions

Winemakers have a small comfort zone where MLF thrives. Around 18–22 °C the bacteria are active and steady. If the cellar is too cold, the process crawls. If pH is very low, the bacteria struggle. If sulfur dioxide is added too early or too high, MLF can stall entirely.

Two practical notes:

-

In young Chardonnay, a warm, steady cellar often leads to a complete, clean conversion with round texture.

-

In high‑acid varieties like Riesling or certain cool‑climate reds, many winemakers keep temperatures lower and manage sulfur carefully to prevent MLF so the wine stays bright.

Where you notice it in the glass

The first thing most tasters feel is texture. Wines after MLF tend to feel smoother and less angular. The second is aroma. Diacetyl, if not scrubbed by lees contact or time, can show as butter, popcorn, or butterscotch. Some producers love a whisper of it for richness. Others keep it nearly invisible by letting the wine rest on lees and minimizing oxygen.

You will often see the effect in Chardonnay, but red wines like Pinot noir also go through MLF for stability and mouthfeel. Aromatic whites such as Sauvignon Blanc or Riesling commonly avoid it to keep citrus drive and cut.

Winemaker choices that shape the outcome

Timing matters. Some winemakers co‑inoculate, starting MLF during or right after primary fermentation so the wine moves smoothly from one phase to the next. Others wait, letting primary finish and then encouraging MLF later. Co‑inoculation can save time and sometimes produce a softer diacetyl profile. Sequential MLF gives more control if you want to taste the base wine first.

Vessel matters too. MLF in barrel can taste different than in tank. Wood allows tiny oxygen exchange and provides a home for bacteria in the pores, which can encourage a rounder, more integrated feel. Tank MLF tends to be cleaner and more neutral.

Lees and oxygen management are the quiet tools. Stirring lees can reduce noticeable diacetyl by reabsorbing it, while limited oxygen helps keep flavors fresh. Sulfur additions wait until MLF is complete if the goal is a full conversion.

Troubleshooting, briefly

If MLF stalls, winemakers often check three basics: temperature, pH, and free SO₂. Warming a wine into the 18–22 °C zone, ensuring pH is not too low for the culture, and easing sulfur levels can restart a stuck conversion. In some cases, introducing a robust Oenococcus oeni culture helps finish the job cleanly.

Style decisions: when to use it, when to skip it

Use MLF when you want softer edges, a rounder mid‑palate, and a calmer sense of acidity. Classic examples include many barrel‑aged Chardonnays and nearly all still red wines for stability and texture.

Skip or limit it when the wine’s identity depends on drive and snap. That often includes Riesling, Chenin Blanc in certain styles, high‑tone Sauvignon Blanc, or any white meant to be razor‑fresh.

Pairing and serving notes

MLF‑softened wines tend to flatter creamy sauces and roast chicken, because the roundness in the wine meshes with richness on the plate. High‑acid, non‑MLF whites shine with briny oysters, goat cheese, and salads with citrus dressing.

Serving temperature shapes perception. Cooler service heightens cut and mutes butter notes; slightly warmer service brings texture forward.

Myths and quick truths

You do not need obvious butter to have completed MLF. Diacetyl can be low or masked by lees. You also do not need new oak; plenty of neutral‑oak wines complete MLF and stay focused. Most red wines undergo MLF for microbial stability even when the aroma does not shout about it.

The take‑home

Malolactic conversion is a shaping tool. By turning malic into lactic, it softens acidity and can add a creamy accent. The best examples keep fruit and place in focus while using MLF to round the edges. When you like that gloss with roast chicken or a pan‑sauce fish, you are enjoying the quiet work of bacteria done right.

Sources

-

WSET Level 4 Diploma in Wines – D1: Wine Production

-

WSET Level 4 Diploma in Wines – D3: Wines of the World

-

Wine Production: Vine to Bottle (Grainger & Tattersall)

-

Wine Tasting: A Professional Handbook, 2nd ed. (uploaded resource)

-

Understanding Wines: Explaining Style and Quality (WSET) (uploaded resource)

-

Oxford Companion to Wine (Harding, Robinson, Thomas), 5th ed. (uploaded resource)

Comments